Quantum computing offers a significant change in how we solve problems. Machines that use the uncertainty and randomness of quantum physics could eventually outperform even the strongest classical supercomputers. This shift could reshape areas like finance, artificial intelligence, and materials science.

For cybersecurity, however, the immediate concern is not opportunity. It is trust.

Modern digital security relies on encryption, the quiet, unseen system that protects payments, communications, identities, software updates, and records. If quantum computers become powerful enough, they could threaten this foundation by breaking cryptographic systems that we currently consider secure.

This doesn’t mean quantum computers are coming tomorrow. However, it does suggest that the ideas behind today’s encryption are already time-limited. Since changes in cryptography can take years to implement, we must start preparing long before the threat becomes real.

Why Quantum Computing Is a Cybersecurity Issue

The internet relies heavily on public-key encryption and digital signatures to ensure confidentiality and authenticity. Algorithms such as RSA, Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), and Diffie-Hellman are secure not because they are unbreakable, but because breaking them takes an impractical amount of time using classical computers.

Quantum computing changes this situation.

Unlike classical systems that process bits as either 0 or 1, quantum computers use qubits, which can exist in multiple states simultaneously through superposition and become linked through entanglement. This lets quantum systems explore many possible solutions at once instead of one at a time.

That difference matters because modern encryption is built on mathematical problems designed to be slow to solve. Quantum algorithms change the math itself.

How Quantum Algorithms Undermine Today’s Cryptography

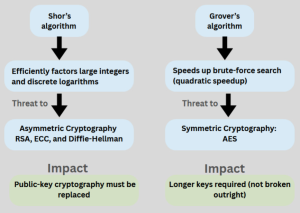

Two quantum algorithms are central to the cybersecurity discussion.

Shor’s algorithm can factor large integers and compute discrete logarithms exponentially faster than classical methods. If run on a sufficiently powerful and stable quantum computer, it could expose the private keys underlying RSA, ECC, and Diffie-Hellman, compromising encrypted data, authentication systems, digital certificates, and software signing.

Grover’s algorithm affects symmetric encryption differently. It does not break algorithms like AES outright, but it reduces their effective security strength, meaning keys would need to be longer to remain secure.

The implication is clear: symmetric cryptography can be strengthened, but public-key cryptography must be replaced.

“Harvest Now, Decrypt Later”: A Retroactive Risk

One of the most serious quantum-era threats is not immediate decryption, but delayed exploitation.

Attackers can intercept encrypted traffic today and store it for years. Once quantum computers reach sufficient capability, that archived data can be decrypted quickly; a strategy known as harvest now, decrypt later (HNDL).

This makes quantum risk retroactive. Information thought to be secure for decades, medical records, intellectual property, diplomatic communications, may already be vulnerable if it is being collected now.

For organizations handling long-lived sensitive data, the timeline of confidentiality matters more than the arrival date of quantum hardware.

What Parts of Cybersecurity Are Most at Risk

Because public-key cryptography is deeply embedded, quantum risk cascades across the digital ecosystem.

Key areas of exposure include:

- Public key infrastructure (PKI) and certificate authorities

- TLS, HTTPS, VPNs, and secure tunnels

- Digital signatures and software update mechanisms

- Single sign-on and federated identity systems

- Secure email in regulated environments

- Blockchain and cryptocurrency systems

- IoT devices and embedded controllers

- Operational technology and critical infrastructure

Many of these systems were designed to last decades and were never built with cryptographic agility in mind, making rapid migration difficult.

Cryptocurrency as a Case Study in Quantum Risk

Blockchains such as Bitcoin and Ethereum provide a clear illustration of quantum impact.

Cryptocurrency security depends entirely on cryptography. Ownership is defined by private keys, and transactions are authorized through digital signatures. If a quantum computer could derive private keys from exposed public keys, it would undermine the trust model at the heart of these systems.

This threat is not immediate. Breaking blockchain cryptography would require quantum computers with millions or billions of stable qubits, far beyond current capabilities. Most experts estimate a five-to-fifteen-year window.

However, public keys exposed today remain visible forever on immutable ledgers. Early address formats and reused keys are therefore long-term liabilities, reinforcing the harvest-now-decrypt-later problem.

What makes cryptocurrency important in this discussion is not panic, but visibility. It demonstrates how cryptographic disruption looks in real life, with clear incentives and measurable consequences.

The Readiness Gap: Awareness Without Action

Despite widespread awareness, preparation remains uneven.

Surveys of cybersecurity, governance, and digital trust professionals show that while most believe quantum computing will break current encryption standards, only a small minority say their organizations treat it as a near-term priority. Many have not discussed it at all.

Knowledge gaps are equally concerning. Only a small percentage report a strong understanding of post-quantum standards, even though they have been in development for over a decade.

This disconnect matters because cryptographic migration is slow. Waiting for certainty often means starting too late.

Post-Quantum Cryptography: The Practical Defense

The most immediate response to quantum risk is post-quantum cryptography (PQC).

PQC does not rely on quantum hardware. Instead, it uses classical algorithms based on mathematical problems believed to remain hard even for quantum computers. These include lattice-based, hash-based, and code-based constructions.

Standards bodies such as National Institute of Standards and Technology have led global efforts to standardize post-quantum algorithms, providing a foundation for governments and enterprises to begin migration.

PQC is designed to work with existing networks and protocols, making it the most practical path for large-scale adoption.

Quantum Cryptography: Security Based on Physics

Quantum cryptography is often confused with post-quantum cryptography, but they are fundamentally different.

Quantum cryptography relies on the laws of physics rather than mathematics. Techniques such as quantum key distribution (QKD) use quantum states of light to establish encryption keys in ways that make eavesdropping detectable.

In theory, this makes interception physically observable.

In practice, QKD requires specialized hardware, controlled infrastructure, and faces distance and scalability challenges. As a result, it is currently limited to high-assurance environments rather than the general internet.

The future of cybersecurity is likely to involve both:

- post-quantum cryptography for broad, scalable protection, and

- quantum cryptography for specialized, high-security use cases.

Beyond Cryptography: Quantum Computing, AI, and Cybersecurity

Cryptography is not the only concern.

Quantum computing may also enhance artificial intelligence, accelerating machine learning, optimization, and pattern discovery. This raises the prospect of quantum-enhanced AI reshaping both cyber offense and defense.

Potential offensive uses include:

- faster vulnerability discovery,

- more adaptive malware,

- large-scale social engineering and deepfake attacks.

Defensive applications could include:

- improved anomaly detection,

- faster incident response,

- more effective vulnerability remediation.

While quantum-enhanced AI is not imminent, it reinforces a central theme: advantages may shift quickly once technical thresholds are crossed.

Why Preparation Must Begin Now

Quantum risk is not about predicting a single “Q-Day.” It is about data lifespan, system rigidity, and coordination.

Cryptographic standards take years to finalize. Infrastructure upgrades take even longer. Data stolen today does not expire.

This is why agencies such as Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, National Security Agency, and the UK National Cyber Security Centre urge organizations to begin planning now, through cryptographic inventories, crypto-agile system design, and long-term migration roadmaps.

The goal is not perfection. It is resilience.

Quantum Cybersecurity Is a Collective Challenge

No single organization can solve quantum risk alone.

Migration to quantum-safe security requires coordination across governments, vendors, cloud providers, software ecosystems, and long-lived infrastructure. Standards must align. Supply chains must move together. Legacy systems must be managed realistically.

Quantum cybersecurity is therefore not just a technical challenge. It is a governance and coordination problem.

Conclusion: The Beginning of a Long Transition

Quantum computing is often seen as either something far off or a looming disaster. The truth is somewhere in between those views.

Large-scale quantum computers that can break modern encryption may still be years away. However, the steps needed to prepare for them take just as much time.

Some cryptographic assumptions will fail, and new ones will take their place. Some advantages will shift to attackers while others will go to defenders. The organizations that do best won’t be the ones that guess the timelines accurately, but those that recognize change is certain and plan for it.

There is one clear fact about quantum computing:

This is not just one event; it marks the start of a long transition. In cybersecurity, transitions reward preparation much more than certainty.